HISTORY

Mana whenua

Māori have had a long association with the Abel Tasman National Park dating back more than 600 years. Archeological evidence shows most occupation was seasonal, with iwi (tribes) living along the coast, gathering kaimoana (food from the sea) and growing kumara on suitable sites.

The first known iwi were the Ngai Tara who came from the Wellington area. Around 1600A.D, Ngāti Tumatakokiri arrived from the Marlborough Sounds and gradually spread as far as Karamea. The people of Te Ātiawa and Ngāti Rārua also recognise the ancient people of Waitaha who tribal traditions say came to the area from their ancient homeland Hawaiki.

The region’s abundant food and proximity to the West Coast’s pounamu (greenstone) made it attractive to invading iwi and around 1800 Ngāti Tumatakokiri were conquered by Ngāti Apa from the North, Ngāti Kuia in the east, and Ngāi Tahu from the South.

In 1828 the Taranaki and Tainui tribes that were part of Te Rauparaha’s confederation swept through the region. The local tribes were almost completely destroyed with the area then settled by Te Ātiawa, Ngāti Rārua and Ngāti Tama.

Local iwi continue to have a strong relationship with the park as kaitiaki or guardians, working closely with Project Janszoon and DOC. Pou whenua are being erected at significant sites in the park to celebrate the stories of ancestors with links to the Abel Tasman and surrounding areas.

ABEL JANSZOON TASMAN

Abel Tasman was a Dutchman and was in command of two vessels that belonged to the Dutch East India Company. The Company dispatched Tasman to look for the fabled Southern Continent in August 1642. Eventually, he sailed across the sea, which now bears his name, and arrived off the coast of New Zealand on 13 December 1642.

On 18 December, Abel Tasman and his crew anchored in what is now known as Golden Bay, a short distance from the Māori pa at Taupo Point. It is thought Ngāti Tumatakokiri warriors came out to inspect the ships by waka and the resulting skirmish resulted in the death four of Abel Tasman’s men. The local māori also suffered casualties and Tasman never landed in the area.

He named the area Murderers Bay and fled north, anchoring near the Poor Knights Islands but never actually setting foot on land.

CAPTAIN JAMES COOK

It wasn’t till 128 years later that Captain James Cook visited the area. But he also never landed. He sailed past the entrance to what is now Tasman Bay, on the 29th of March 1770 and again in May 1773. Due to unfavourable winds Captain Cook never risked closer inspection.

DUMONT D’URVILLE

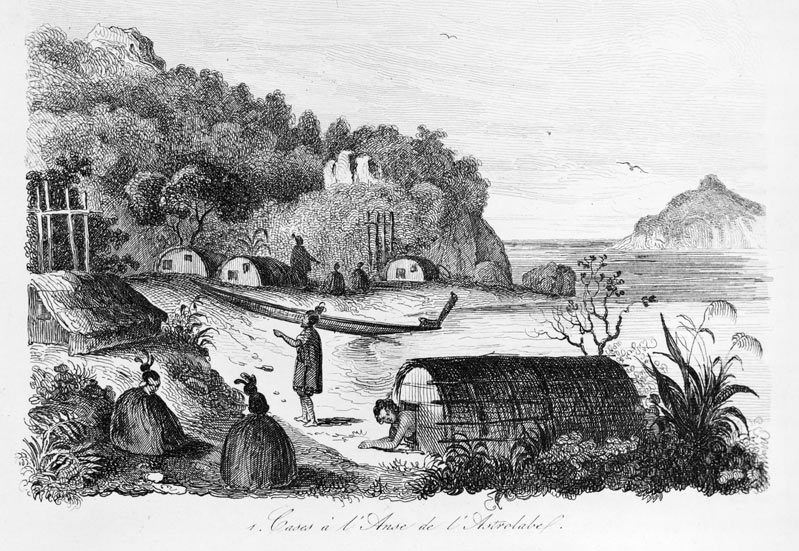

French explorer Dumont D’Urville’s ship, the Astrolabe, anchored off the coast of the Park on the 16th of January 1827. D’Urville named the sheltered part of the coastline south of Anchorage the Astrolabe Roadstead, a name still used today. He also named the nearby island “Adele” after his wife. In 2014 the name was officially changed to Motuareronui Adele Island.

During his week in the area D’Urville established good relations with local Māori, who, according to John and Hilary Mitchell in Te Tau Ihu o te Waka (Volume 1) were Ngāti Kuia and/or Ngāti Apa, along with Ngāti Tumatakokiri.

D’Urville and his crew explored many of the bays and headlands around the Roadstead, naming landmarks like Watering Cove, Simonet Creek and Coquille Bay.

A chart from D’Urville’s visit shows six huts at Torrent Bay and he, and others like early surveyor John Wallis Barnicoat, recorded Māori in small settlements at many spots in the Park like Mutton Cove, Te Pukatea Bay, Whariwharangi, Awaroa, Marahau and Adele and Fishermans Islands.

EUROPEAN SETTLERS

With the arrival of the New Zealand Company, Māori lost control of much of their land. Land now within the National Park boundaries were subdivided and sold to settler families during the 1850’s and 60’s.

Settler families including the Hadfield, Huffam, Gibbs, Tregidga and Sixtus families worked the land in different ways – farming, boat building, the bark trade and quarrying. Native bush was cleared by fire, or milled.

However, this was not good farming land. The area was difficult to access, had poor soils and the terrain was mostly challenging.

Many of the 113 different weed species in the park are likely to have been planted by the settlers as a reminder of home. Unfortunately they much preferred the national park environment and these days a lot of time is spent trying to control them.

TOWARDS

NATIONAL PARK

STATUS

During the period between 1895 to the mid 1930’s, various parts of the area that are now within the Park were designated as reserves. In 1920/21 a large area of the land was designated as provisional State Forest pending further investigation.

PERRINE MONCRIEFF

It was the rumour of a proposal to establish a sawmill at Totaranui in 1937 that prompted environmental campaigner and Nelson resident, Perrine Moncrieff, to start pushing for the area to be designated a National Park.

A fire on land at Torrent Bay in 1941 spurred Moncrieff into linking her proposal to declare the area a National Park to the upcoming 300th anniversary of Abel Tasman’s discovery of New Zealand.

Prime Minister Peter Fraser announced the Government decision to set aside nearly 38,000 acres for the Abel Tasman National Park (ATNP) in November 1942. The area comprised 21,000 acres of provisional State forest, 14,354 acres of Crown land and 1,368 acres of scenic and other reserves.

Queen Wilhelmina of the Netherlands agreed to be patroness of the Park and sent a delegation to attend the official opening on 19 December 1942. This opening was meant to take place at Torrent Bay, but rough seas forced them to hold the ceremony in Kaiteriteri instead. After speeches by government and local representatives, the Governor General, Sir Cyril Newall, declared the Abel Tasman National Park open.

THE PARK OPENS

Initially the Park was administered by the Abel Tasman National Park Board and in the mid 50’s the Abel Tasman Coast track was formed with huts gradually built over the next two decades.

In 1976 the Wilson family began Abel Tasman National Park Enterprises taking passengers on the first scheduled services from Kaiteriteri to Bark Bay.

In 1980 the Department of Lands and Survey began administering the Park. The Department of Conservation (DOC) took over responsibility for the management of the Park in 1987.

The 1835 ha Tonga Island Marine Reserve was created in 1993.

At 22,530 ha the Abel Tasman is New Zealand’s smallest national park and also one of its most visited with an estimated 300 thousand visitors in 2017.

As kaitiaki and guardians, Ngāti Tama, Ngāti Rārua and Te Ātiawa work closely with DOC, the Abel Tasman Birdsong Trust and Project Janszoon towards restoring the ecology of the Abel Tasman.

PROJECT JANSZOON

Project Janszoon, a philanthropic trust named after Abel Janszoon Tasman, was launched in 2012.

The project was unique in that it is a landscape scale restoration project undertaken by the Crown and a private trust. Committing to spend up to $25 million over the life-time of the project, Project Janszoon works with DOC, the Abel Tasman Birdsong Trust, the community and local iwi to restore the ecology of the Park on a variety of fronts.

In 2015 this collaborative approach was recognised when Project Janszoon was honoured to win both the Supreme Award and Philanthropy and Partnership category, at the 2015 Green Ribbon Awards.

ABEL TASMAN BIRDSONG TRUST

Local conservationists formed the Abel Tasman Birdsong Trust in 2007 with a vision of bringing back the birdsong to the Park. A partnership between the commercial operators, community and DOC it is unique as all the major commercial operators working in the Park contribute funds in the form of a “birdsong fee”.

Birdsong Trust members have worked with DOC to make Motuareronui Adele Island predator free, returning toutouwai/robin and tieke/saddleback to the island. Other projects include trapping, wasp, wilding pine and weed control and native tree-replanting.