John Henderson locating transmittered kākā after release. Photo by Ruth Bollongino

Popular media understandably celebrates the successes of conservation milestones. These celebrations are valuable to remind us of progress and to encourage support. It is important though to also remember the hard work and the frustration that gets us there. An example with Project Janszoon is the checking of stoat traps over 15,000 ha of rough country every month. These workers get wet and sore continually yet their reality seldom features on such occasions.

Project Janszoon released its 8th captively raised juvenile kākā in April but I thought it might be interesting to look behind the scenes and review events in getting there. It hasn’t all been plain sailing.

Firstly there was two years of spirited discussion on where we should source kākā from if the species was going to be re-established in the park. Discussion covered the genetic variability, or lack of, up and down the country; whether likely sources might be too inbred, whether cropping from other sources might threaten the viability of a wild population, whether kākā used to migrate across Cook Strait, the morphometric cline in wild populations from north to south and so on. All of this debate was aimed at ensuring the released kākā were as similar as possible to those that are still surviving and yet also wanting to obtain enough birds to guarantee a viable new population. In the end permission was granted to release up to 100 birds over a 10-year period, sourcing these from the existing captive population of South Island kākā whilst also attempting to maximise the input of kākā genes from the top of the South Island.

It has been assumed that the few surviving kākā in Abel Tasman are all male birds because of the known selective predation of nesting females. Therefore to increase the chances of having their genes in the new wild population the first 8 birds to be released were all females. We didn’t want to release any captively raised males that might compete with the old resident males.

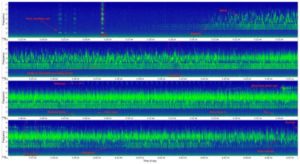

An opportunity to increase the input of kākā from northern South Island came in spring 2015 when kākā at Nelson Lakes began breeding in anticipation of abundant food for their young from an imminent masting of beech seed. Having obtained endorsement from iwi and from DOC at Nelson Lakes staff were able to capture kākā, fit transmitters, find nests, protect those nests from predation and finally collect some of the young for addition to the captive population. Described in one sentence but the field work alone took two experienced kākā biologists, Ron Moorhouse and John Henderson, several months. Despite knowing the area from previous work there was no escaping the trials of pre-dawn starts, having to access the canopy by rope and harness and of course the inevitable wasp nests. By late January five chicks were removed from the wild and taken to Natureland for raising by their professional aviculturists.

So far so good. DNA testing of these chicks showed they were all male, then one had to be euthanased as it was suffering from metabolic bone disease which had developed while in its wild nest. Another of the juveniles died from a respiratory infection. That leaves us with three males as a contribution to the captive population.

Meanwhile it hasn’t been easy for the eight female kākā released into the park. Of the four released in October one died within 10 days. Close monitoring of these transmittered birds meant the carcass was retrieved promptly and subsequent tests reveal lead poisoning. This is most likely related to lead in the galvanising of some aviary components—investigations are continuing. And another bird has vacated the park, last seen in downtown Takākā. The second release in April of this year was similarly fraught. Two of these juveniles have now been found dead and we are we are waiting for lab test that may determine the cause of death, and DNA results from any predator saliva which may still be on the corpses. The distress at these deaths is not felt just locally—they come from aviaries around the South Island where school children have been involved with the naming and farewelling of these birds. Another juvenile is proving elusive and its presence is a little uncertain.So at the time of writing we have just three juvenile females known to be alive and well and still within the intensively managed area of the Wainui catchment. An optimistic outlook is that these three will survive and mature ready for breeding with the old boys of the park sometime soon. Meanwhile more releases are being scheduled to ensure a strong and diverse critical mass for this new population. We know that kākā used to be very abundant in the park, we now know that kākā will flourish when stoats and possums are controlled and we also know that those pests are being well controlled by Project Janszoon. There is no doubt we are on to a winner here—we just have to learn from these frustrations in the early days.