Finding the right balance: Recovering weka are taking their toll on native snails

By Ruth Bollongino, Project Janszoon Science Advisor

At first glance, it is a wonderful success story of how pest control can bring back a native species: in Te Tauihu, the Top of the South, weka were extremely rare during the 1980’s and 1990’s and faced local extinction. In 2006, 30 weka were released at Totaranui because weka numbers were very low in the Abel Tasman National Park.

Project Janszoon started to implement a park-wide stoat trapping network in 2012. At that stage weka were still so rare that rangers reported each sighting. But that changed quickly. Weka are prolific breeders and can produce four clutches a year with up to 4 chicks each. Bird monitoring suggests that each year weka numbers doubled, if not tripled, in the areas they occupied.

Weka started spreading along the Abel Tasman coast and slowly made their way uphill into the higher elevation areas of the park, where they arrived around 2016. Project Janszoon is carrying out mark-recapture monitoring of carnivorous land snails, Powelliphanta hochstetteri and Rhytida oconneri at two sites in this area.

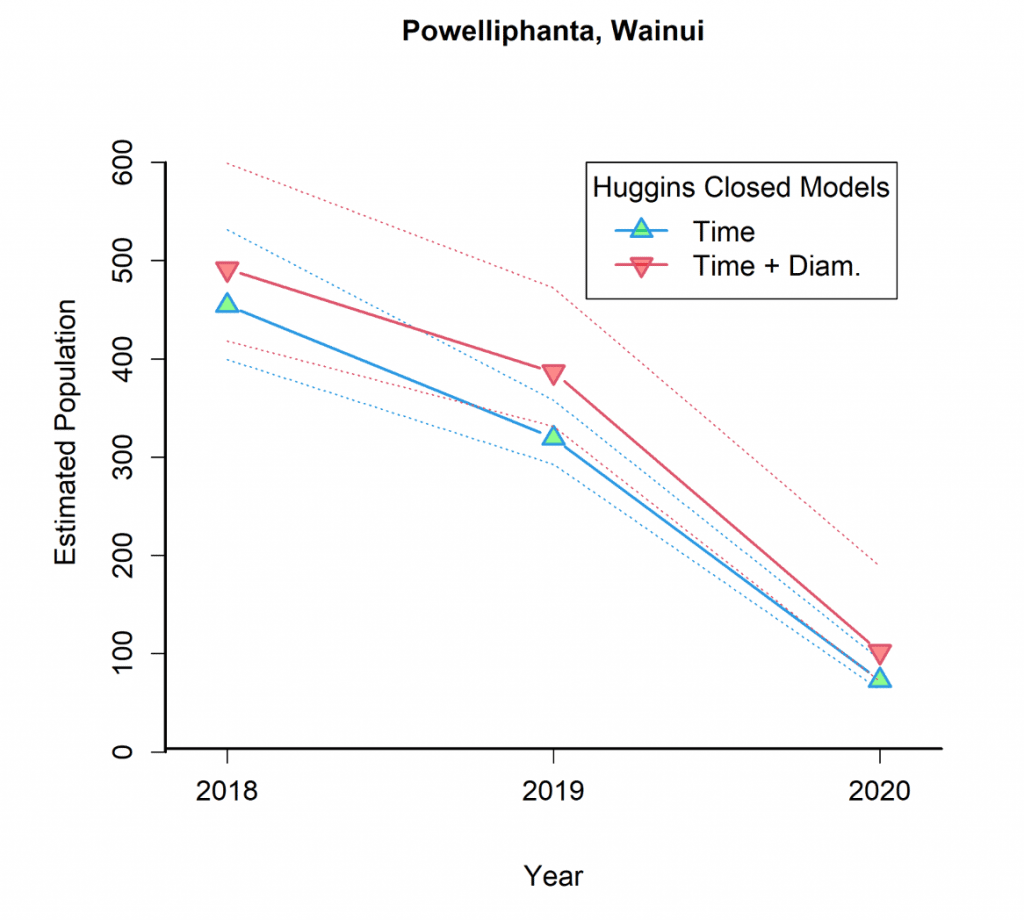

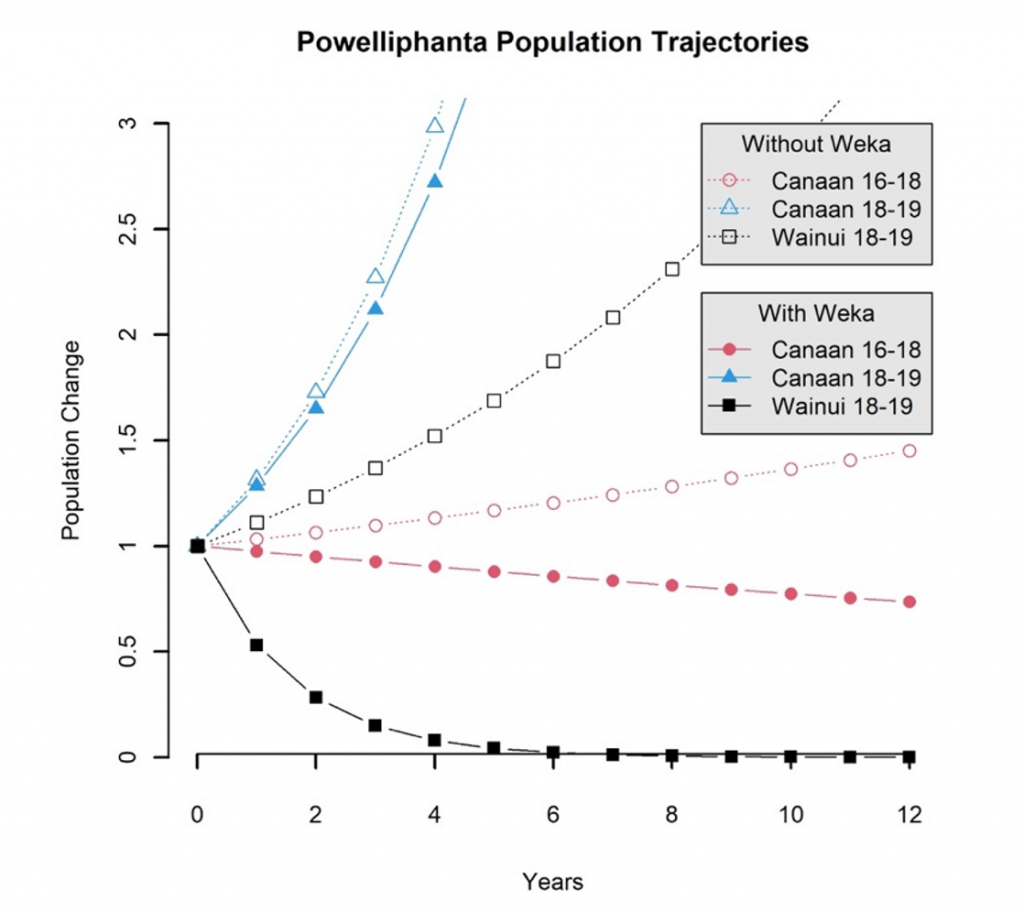

One of the plots is located near Wainui Hut in the Upper Wainui valley. When monitoring started at this site in 2018, the results showed a young, recovering snail population of 450 snails on the 70x70m plot. One year later, a clear downward trend was observed, with only 320 snails estimated on the plot (Fig.1) A high number of fresh shells indicated a lot of the snails had died recently, with half showing a hole near the aperture which identified weka as the predator (Fig.2). The trend has continued in 2020 with the snail population now down to 73 animals (Fig.1), and even more shells showing weka predation. If this trend continues, the local snail population could go extinct within the next four years (Fig. 3).

Although weka are natural predators to snails, the abundance of both species is out of balance. Snails are also being challenged by exotic predators, habitat degradation and global warming. Weka benefit from predator control and probably have an increased carrying capacity as they feed on rodents in the area. Additionally, most of their natural enemies, like the Haast eagle, laughing owl and Eyles’ harrier, are now extinct.

There are some indications that snails are less affected by weka predation in karst habitat with rocky surfaces. An area at Canaan in karst habitat is currently being monitored and the results will be reported soon.

This case study demonstrates the importance of sensitive outcome monitoring that informs conservation managers at an early stage to ensure that adequate measures can be taken to safeguard our natural heritage. While a solution to protecting snails in the presence of high weka numbers is not obvious, the monitoring information provides a necessary indication of the scale and rapidness of the changes so appropriate management options can be considered.

Figure 1: Population size and trend of Powelliphanta hochstetteri at the Wainui mark-recapture plot using two different models for the simulation. Dashed lines indicate width of the 95% confidence interval.

Figure 3: Trajectory of Powelliphanta hochstetteri trends showing that snails at Wainui are facing local extinction if weka predation continues at high levels. The snail population in the karst environment of Canaan is less impacted by weka.